A Wednesday : Moses’ Ark, Olympics, vaccines, Omelas, genetic fallacies, Expressionism, poetry in wild forests.

Moses and the Ark

We’re reading this collection of thirteen Bible stories entitled Moses’ Ark (Alice Bach and J. Cheryl Exum, 1989). It’s an interesting approach that finds an area between early childhood and full-on “adult” to present often-familiar stories with a mix of scholarly rigor blended with extrapolated dialogue and personality. One of my favorite parts, though, is the note included at the end of each story that provides some additional context in terms of language and meaning.

The Bible is simply an incredible meta-book. History, poetry, self-help, life hack, narrative, philosophy, religion…as a family of faith, it is a very important work not only for these reasons and as a beautiful piece of literature, but as an inspired work, interpreted by humans, from God. Or of God.

That being said, we don’t read or study it as a replacement for a science textbook. We don’t embrace the stories as a reminder that we’re all right and everyone else is wrong. We don’t read the heroes for a primer on how to be perfect.

We read the Bible because there is so much good to get out of it. We get a lot about Laws from the Old Testament and a lot about Love from the New. It’s a great representative dichotomy, or juxtaposition, that life is often made up different elements that sometimes work together, and sometimes work at different extremes to help keep us in balance. That being said, of course, Jesus the Christ did say that one thing I hope to bury deep in our family’s soul and heart:

”…Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind…the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.”

The Bible’s both simple and complex. Simple in the sense of…well, read Jesus’ words above. Complex in the sense of…well, just about everything else.

I deeply respect those who can acknowledge the complexity of the Bible’s meanings and face up to the tough questions embedded throughout. I’m not someone who approaches the Bible from purely historical, literary, academic, philosophical, or intellectual interest, although those are all big reasons it draws me in. I also believe in a supernatural aspect of it; the idea of a supreme being whose being is reflected on Earth and its inhabitants. This belief is at odds frequently with my interest in science, logic, philosophy, and asking questions in general, rather than accepting something simply because it’s contained in a book I believe in and therefore am supposed to unquestioningly accept anything unexplainable as something beyond the realm of our comprehension.

Here’s the thing: it’s complicated. We are a family who asks questions together and doesn’t answer every difficult question with a variation of “because it’s in the Bible.”

The Bible is made up of Words.

Our family reads those Words in English, which is the language we are most comfortable understanding.

Those English Words have been translated from ancient Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

The original writers who wrote those Words wrote them down over long periods of time, often long past the happening of the events described.

There are scholars who talk about the discrepancy in the Gospels as being a positive thing. Something about how the slightly differing accounts provide greater proof of there not being collusion amongst authors, et cetera.

For me, I have no quandary with accepting the Bible as inspired words, yet also recognizing the basic fallacies and errors people make in interpreting events. I can accept the not just probable, but the almost-certain amount of corruptibility that enters into informational transactions, whether conscious or unconscious, deliberate or inadvertent, concrete or a subtle nuance of one word over another that, like a skyscraper foundation off two inches at the bottom, ends up a far bigger error the further down the line. People struggle to accurately describe even events they witnessed firsthand in the moment. So when I look at the span of hundreds of years these words were written over, and the process of multiple words from multiple authors, often culled from oral historical traditions, then going through processes of translation, interpretation, culling, editing, revision, ex cathedra determinations of provenance and legitimacy, and finally ending up in our hands, in front of our eyes in the manner we see today…how could we do anything but continue to ask good questions, in good faith, about complicated matters?

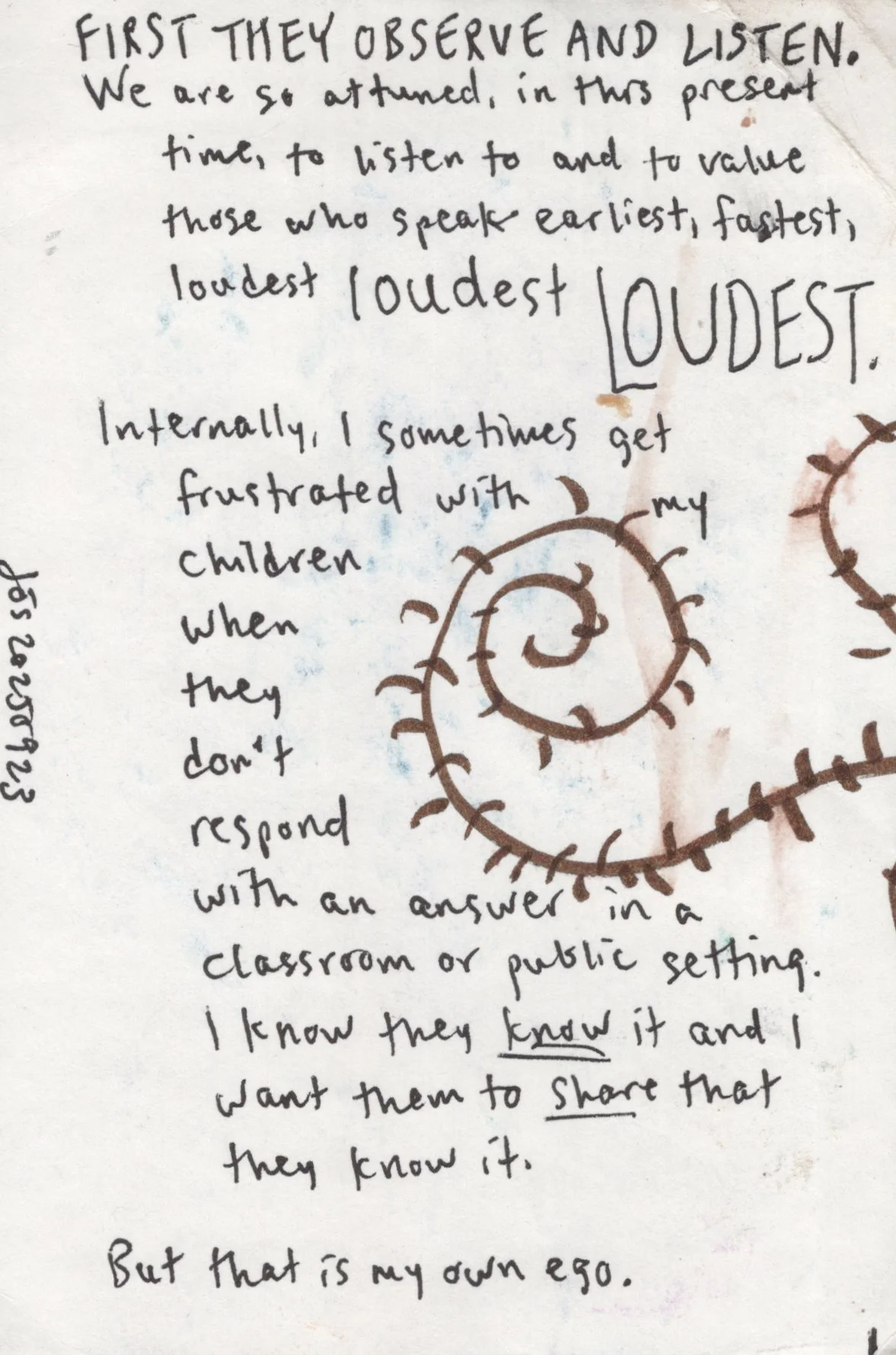

And that is also where I think it is so important to grasp the importance of words and language. Today more than ever. The words we choose to use and interpret matter. The syntax, the choice of one word over another, the decision to phrase something concretely or mysteriously…these things matter. Words matter. Language matters. Language allows us to articulate the pictures in our heads; the way that we form opinions and make life philosophies about how we’ll interact with the world around us and who we’ll vote for and what we’ll support and what we’ll fight for or against.

Language is integral to how we communicate, record history, form relationships, and synthesize the swirl of life surrounding us. We hear so much about how we live in a visual world, how images and pictures and photographs, the visual, is what’s important. Not taking away from the visual. Except…we still use words and language to shape our relationships to the visual. As humans, we still prop up our relationships with the visual with words.

So when I read the forward to Moses’ Ark and read the authors’ words about why they use the word “ark” instead of the familiar “basket,” I got excited. Going back through the translations and how the story is written in the original Hebrew…it gives an entire new context.

And in a big sense, is a wonderful reminder of how our perception of anything historical is colored and affected by the choices people, humans, have made in concretely interpreting specific words across time, geography, and language, and in a general sense of filtering, culling, arranging, and cohesively putting together narratives funneled through their own understanding. It provides a bit of humility in recognizing all the difficulty so many of these stories went through in their journey to rest on the page before us in their current incarnations.

And a big reminder that it’s okay to keep asking questions about difficult-to-understand topics and stories.

Go Team!

There were different points in my life where the Olympics were a big deal. I remember having a crush on Katarina Witt at the 1988 Calgary games, her inimitable style gliding her through the air on triple axles set to Michael Jackson.

And then these ones arrived. The ones in China, and we keep forgetting to pay any attention. Not consciously. Just forgetting. It feels like such a weird thing, like forgetting to watch the Super Bowl, or forgetting to watch the World Series or March Madness (all things I’ve also done).

There’s something that feels good though about being tuned out to big things.

I had it on earlier this morning, and our 11-year old has reminded me of the joy in communal sports watching. He chooses his allegiance primarily based on a) the coolnesses of the competitors’ names and b) the coolness of the country competing.

There was a lot of yelling when Denmark won something a bit ago. Luge?

Either / Or

Sometimes a mediocre cup of coffee is almost worse than a straight-up bad one.

When something’s really bad, it feels okay to either toss it, or gulp it down with a chest-thumping bravado and a feeling that you’re ‘…taking one for the team.’ This is a feeling roughly analogous to someone announcing proudly on a Monday morning that they ‘…powered through that new Netflix series,’ as if it is a life obstacle that has been successfully surged past and deserves accolades.

Health - Vaccines

We talked about Edward Jenner and his early work. Vacca is Latin for cow. Mr. Jenner was investigating cowpox, or ‘smallpox of the cow.’ Eventually his work led to the world’s first (official) vaccine. Thank you, Ed.

Literature - The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas

After you read this 1973 Ursula Le Guin short story, you will never forget it. Consider it a sort of companion think-piece to Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery.

There is a city. The city of Omelas. The residents lead happy, joyful, beautiful, productive, meaningful lives. All is good and egalitarian. There’s just one thing…

And that one thing will have you thinking deeply about our acceptance of reality, and how willing we are to accept the price of our present happiness if the expense is at that of other people or the future.

Chilling. A profound meditation on compassion and call to arms for empathy and self-reflection.

ELA

I proofed our 14-year old’s outline for an upcoming paper on climate change she’s doing in collaboration with a colleague.

I made a few notes and observations, and thought again of the ways in which we convince ourselves to forget or ignore that which isn’t convenient.

Infanticide in the time of Pharaohs (and continuing, in some countries, into modern times).

The fictional city of Omelas and the societal pact everyone makes in order to sustain a collective happiness.

Climate change and the way we reject or ignore the realities of science, because we live in the present and for most of us, life is more convenient to continue our patterns of living and purchasing than to make changes that may benefit the collective in the future, but do not benefit us individually in the present.

Life is challenging sometimes. And it should be.

Poetry

I read some William Carlos Williams over lunch. He never gets old. I just love his tiny descriptions of beautifully bland moments in life. Simultaneously whimsical and profound.

We also took to the woods to share and present some Emily Dickinson, John Donne, and Moana songs from our makeshift stage: a fallen tree, once giant, now providing a platform for expression deep in the forest.

Also, a goat joined in, head butting various trees as an artistic statement of purpose. Or maybe it just felt good.

Reason & Rhetoric - Genetic Fallacy

A Genetic Fallacy argument refers to the origin of a source. Nothing to do with biology. In other words, Volkswagen was a company started in Nazi Germany. Is it a fair position to describe it as an evil company because of its origin 80-some years ago? A relevant example might be:

“You can’t believe anything the media says, they’re all fake news.”

In other words, a person chooses to accept or reject a claim based on where it originated or who it came from, rather than on the quality of the information itself.

This is a difficult one for me, because there are plenty of sources I dismiss automatically as untrustworthy, based on historical patterns of dishonesty, inaccuracy, propaganda masquerading as concrete facts, or blatant disinformation-spreading. You have to have some point at which you accept the quality of information as accurate - for example, do you discount Miriam-Webster Dictionary, or Encyclopedia Brittanica as unreliable because you don’t like their definition of a word or their phrasing of a particular entry?

At some point, we must rely on some form of genetic provenance and its reliability simply in order to assess the information that an argument is based on.

But in general, I suppose this is a good reminder to primarily focus on the merits of the information itself, rather than focus on the origin. It’s a hard one.

Note: ad hominem fallacies and appeal to false authority fallacies are sub-examples of genetic fallacies.

Conversations

There was heated disagreement over whether or not raw flour was okay to eat. Thoughts?

Art - Malevitch, Kandinsky, Dix

We’ve continued poring through The Stories of the Mona Lisa (Piotr Barsony, 2012), and our 2-year old gets excited: “Mona…Lisa…oh, that one is scary!”

Barsony’s approach is to take us on a survey of modern art by examining how different artists might have rendered Da Vinci’s masterpiece. The two-year old above is referring to Expressionist Otto Dix’s interpretation. Yes, it is horrifying and scary and makes you feel something visceral, something the Expressionists were great at doing.

We also looked at Wassily Kandinsky’s take on Ms. Lisa; his geometric shapes and interest in the link between color and sound. As Mr. Barsony speculates, wouldn’t it be great to someday be able to listen to Kandinsky’s music, through his paintings and explorations of how colors and rhythms and ibrations interconnect?

Last we examined Russian Suprematist Kaimir Malevich and the excitement he had, in the early days of Revolution, at inventing “…a new kind of painting.” One focused on placing Man at the center of everything, using symbols and geometrics as representative symbols.

Unfortunately, as often happens with revolutions, Malevich discovered that the Oppressed become the Oppressors once Power becomes the changed variable, and found the consequences for doing something daring and different in Art are different than doing the same in Life. He found himself in prison, tortured. Sad. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.

Jumping, wrestling, other physical feats of valor

I was piled upon, and my body suffered many calamitous abrasions and bruises; my internal organs remain largely intact, and upon later examination, there appears to be minimal fractures or bone breakages, and I can still walk, barely.

After almost 15 years of wrestling children, my body is showing the effects of these daily happenings. I hope there’s some important life lesson or life skill they’re getting out of it.

We threw a ball

Literally. We sat around in the living room and threw a ball around before bedtime. It was a good note to end on, and there was laughing.