Literature & Stories : reading fiction for both enjoyment And learning.

I love to read. I do not have judgments to pass on genre or your favorite author or the reason why you should re-read Ulysses every year. If you read fast-paced summer thrillers year-round purely for enjoyment, cool. I have gathered these thoughts, ideas, and suggestions specifically with two things in mind:

This is in reference to fictional works of writing. Although many of this is also relevant to film and television, it is specifically focused on written, narrative works of fiction. In other words, written, made-up stories.

This is written with the idea that you’d like to learn something. In other words, whether by choice or mandate, you’re reading a work of fiction that has more beneath surface than a fast-paced plot and mono-dimensional characters. You’d like to dig a little deeper, you’d like to get something out of it besides adrenaline rush, and you’d like to learn something from what you’re reading.

Again, I love to occasionally read a fast-paced page turner I can forget five minutes after finishing the final page. But I also like to feel that I can read something both enjoyable and challenging. This is what the following is about. Some bullet points and thoughts about reading for a combination enjoyment and learning.

Note: parts of this are my recollections, remembrances, summations, and interpretations of ideas from Thomas Foster’s 2003 How to Read Literature Like a Professor (e.g. “four struggles of humans”). The book is a very readable, much deeper dive, complete with many literary examples and samples, of how to read…well. Highly recommend.

What I’ve jotted here is a starting point. A starting point that will likely lead you to other works, authors, and books that explore these ideas in depth and detail.

Humans organize. So here’s three main categories of fictional writing:

Novels (as well as novellas, novelettes, and short stories)

Poems

Plays

Each of these has differentiating characteristics, but importantly, all three have overlapping traits too.

What sort of overlapping characteristics?

One thing might be that symbols and metaphors carry across genre and category. The color red, for example, has many of the same connotations whether it’s used in a novel, a poem, or a play.

Another common trait is that any sort of narrative (pretty much a fancy word for “plot”) has a character who wants something. They’re on a quest.

What sort of quest?

There are all sorts of quests. Some are external, some are internal. But there’s a recurring pattern in every quest:

A character wants something. This is the protagonist, the person we’re (usually) rooting for and who is the primary character and driver of the story. In universal terms, this is the hero. It might be a single entity, or several, or many. It might be human, or it might some other living being, real or mythical or imagined. Or the protagonist might be anthropomorphic or the personification of some completely brainless, heartless bit of matter. The possibilities are infinite.

This character wants something and they want to go somewhere. This might be a physical act, or a symbolic or internal journey. Basically, they want to change something about their normal world. Maybe because they’ve chosen to, or because they’re being forced to, or for any number of reasons along the continuum. For whatever reason, they need to go somewhere that they’re not.

But it’s a story, which means it’s a quest, which means the character’s normal world is being changed, and because change is difficult and has obstacles, that means…that the character must face down those obstacles. “Facing down” might mean literally facing down, or running away, or hiding, or any number of things. The important thing is that there are things in the character’s (or characters’) way. They’re hindering the quest at different points. Just like the nature of the quest, these obstacles can be concrete and tangible (like aliens or fierce animals or hurricanes) or they can be abstract and internal (anxiety, relationships, anything that makes your head or heart off-kilter).

The character, with the help of others (probably) problem-solves their way through and around these obstacles because the end of their quest is important. Whatever it is, it’s important enough for them to embark on a journey of change in order to satisfactorily achieve the Holy Grail (i.e. whatever their endgame or goal is). They might not achieve it. They might fail in the end. Sometimes stories have sad or unhappy or unresolved endings. But every story features protagonists who are on a quest of some sort, and battling past various obstacles to get there because it’s important.

Canonical

There is some form of normal world in the story. Actually, there’s going to be at least two worlds. One is the world they start in. The other is the world of their quest; the world that changes and launches us into the story.

The world the character is familiar with. The one they start out in. The “normal” world. Doesn’t matter how bizarre or weird it is to us. For the character, it’s their world, and it’s normal, no matter how much they dislike or despise or reject - or love - it. It’s what they know. Until…

The world changes. Something changes their relationship with their normal world. The fancy word for this normal world is the canonical. Something changes the familiar and sets them off on their quest - no matter what type of quest it is - and from that point on, their normal begins to change, and therefore their normal world begins to shift.

One more thing: the canonical, or “the normal world” of the story is not simply the setting. It’s everything that makes up the world: time, era, place, the social world and type of society, culture, the rules and expectations…

Find the clues early / bookending

Pay attention to the beginning. Does the story start with a line of memorable dialog? Does it start with a description of a specific place? Think of great stories you’ve read, and if you start digging into them - and this includes films - notice how frequently we find ourselves, at the end, looping back to the beginning. Perhaps it’s literal: we’re back in the same physical space. More often, it may be symbolic: a reference or allusion to the state of things at the beginning.

Here’s a movie example: The Sixth Sense. No spoilers here, but if you’ve watched the film, you know how it begins, and how some of the conversation and references have a meaning that sort of makes sense early on…but completely makes sense at the end, when we are deliciously treated to how certain things in the beginning are relevant to how things end up. This is an example of bookending: we start with one that holds the plot framework in place at the beginning, and end with one that keeps it tight at the other end; in between, everything is kept in place, in order, and even though the ending bookmark takes us to a different place in the story - a changed point - it also leads us back to how it ties into the beginning.

What’s in a name?

Why is a name chosen? What significance is there? This can lead down a wonderful rabbit hole of name etymology - and provide valuable clues and Easter Eggs about what character’s role in a story might be. What are the associations that immediately come to mind when you read a character’s name?

Rituals and relationships and how people gather

The protagonist, no matter how lonely they are, likely shares part of their life in some way with other characters. They interact in some ongoing way that shows who they are and what they value and what their personality is and the type of world they’re from. There’s literary names for many of these helping characters. For example, there’s Tricksters, Allies, Guardians, Shadows…the important thing is that in almost every story, there will be characters that interact with the Hero, and with each other, in different ways that sometimes meet expectations, and sometimes surprise us.

What are ways in which people gather? Parties, weddings, dinners, dances, graduations…these are a few big ones. And these are ways in which a good storyteller can have various characters or plot threads come together

Learning about how characters share, interact, and connect via rituals is an important way of learning about the characters themselves and the plot that is set into motion.

Look for character reversals

A good author will make you feel something about a character, whether sympathetic or not. A great author will nuance their characters beyond good and bad, beyond single-dimension character traits. Keep an eye and ear out for characters that are written to make you feel deeply early on. Will they get rounded out into a more interesting and complex character? What impact do these reversals have on the plot and how you expect them to unfold or unravel?

The connectedness of stories

Chances are, some stories and some characters feel familiar to you. They should. That’s because writers and poets have borrowed and stole and been inspired by each others’ works for centuries. Same thing could be said for most other disciplines, but there’s something especially beautiful about how this works with stories and characters we love, because it can start to feel like our own sort of quest, as we find and make connections amongst plots and heroes and villains and themes that feel connected across eras and continents and genres.

There’s something beautiful and magical about making these connections.

More on familiarity

I was talking to a 4th grader recently and he was talking about his love of Harry Potter, and eventually our short discussion led back to a discussion of Theseus and the Minotaur…and of how many modern stories have origins going far back to ancient myths, to the Bible, to Shakespeare, and to many other tales that feel familiar. It feels good to start unraveling those threads that connect the contemporary to the classic, and realize how great stories can be remixed and retold and reinvented in a dazzling array of ways.

Read the old tales (understand what myths are)

Myths are stories that explain something about the world in a way that feels familiar in a shared sense to a group of people.

There’s all kinds of great tales that were once created to explain something not-understandable at the time. We may not use these as explanations for phenomena any more, but they still function to both entertain and to provide understanding into how humans respond to things they don’t understand. Many fairy and folk tales tap into the primal fears of the unknown that we still carry, albeit in different ways.

So if you care about stories or storytelling or writing or becoming a great reader, then read up on the old myths.

Read the Bible

If you care about stories or storytelling or writing or becoming a great reader, then do this:

Read the Bible.

It is arguably more filled with rich narratives and complicated characters than any other single book that’s been written. And yes, technically it’s a collection of books. But we bundle them together under the umbrella of…The Bible.

It’s an incredible read. One to read and learn and get something from on different levels. Repeatedly.

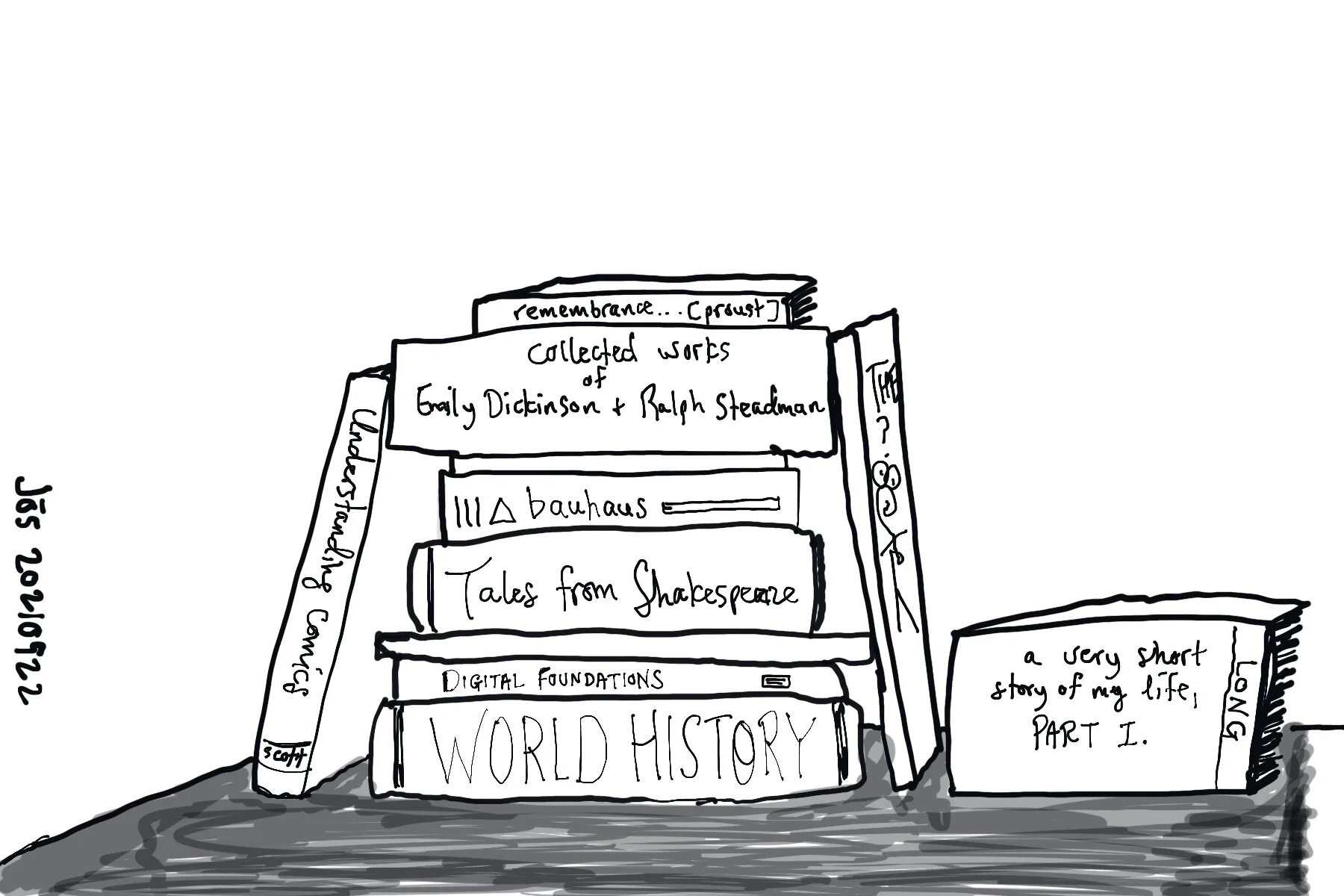

Read Shakespeare

If you care about stories or storytelling or writing or becoming a great reader, then you have to read the Bard at some point. Instead of fighting it, launch yourself with some fun interpretations. If you don’t want to get bogged down with the verse and syntax and style, treat yourself to an easier version of the story first. Then you can work your backward and deeper into the joy of language, the depths of human motivation and relational dynamics, and the dizzying ways in which words can be both poetry and narrative, both specific and universal, both simple and complex.

Charles and Mary Lamb’s 1807 classic Tales From Shakespeare was “…intended for the use of young persons.” I love this, as it is still a tiny bit challenging to follow, if you’re a contemporary elementary school student. But it is a lovely and narrative-focused introduction to Shakespeare that’s wonderful for adults too. Read these, and get to the roots and beginnings of so many archetypes, characters, situations, setups, plots, and even simple words and phrases that are now familiar to us through his works.

Why one word is used over another

In elementary school, there’s a good chance your teacher had you practice finding all sorts of synonyms for different words. In other words, don’t keep using the same word, because it can get boring.

For example, a lot of early teachers will tell students not to write dialogue using: ‘He said, or she said.’ They push students to use stronger, more vivid words, like: ‘He exclaimed,’ or ‘she shouted.’ These are good things to think about and good rules to know when to break. But how about when you notice an author is consistently using the same word to describe something? Is it an accident? Is it because they’re lazy or too tired to look up synonyms? Probably not.

Most likely, a good writer has thought carefully about the meaning attached to that specific word. Consider why they might be doing so. What are the symbols or allusions or historical references or just plain old feelings associated with a particular word, when an author chooses to use it repeatedly?

Repetition, adverbs, and the power of small words and definite articles

Can’t say I gobble up Hemingway for enjoyment. But he could write a sentence. The guy knew how to cut out adverbs like nobody’s business. And he understand the power of simple, small words used repetitively. He did this with great effect to convey ideas, to foreshadow, and to build metaphors and symbols that might have got buried under big words and obtuse phrasing.

Great example: his opening to A Farewell to Arms. 126 words, four sentences. A master class in using ‘the’ and ‘and.’ What’s the different between using a definite article such “the” or leaving it off? How is it different to write “flower” versus “the flower?”

If you’re a photographer, what you leave out (crop) can be as important as what you leave in when you’re framing an image. Same applies to writing.

Do those extra words enhance or distract?

If you’re a reader and a writer…

What is the experience and background and expertise you bring to words? Whatever community or environment or region you grew up in, it had its particular and peculiar sets of words, phrases, and language that you know deeply.

Use that. As a reader, it will connect you to the stories you read. As a writer, it will help connect you deeply and meaningfully to your audience. It means you’re drawing from embedded experience and the language that accompanies that experience.

The four great struggles of humans

Thomas Foster, in chapter 9 of his engrossing book How to Read Literature Like a Professor, breaks down and talks in detail about the four great struggles. I’m using his list below; read his book for in-depth advice on reading for understanding.

The four great struggles of humans are the need to…

…protect your family.

…keep your dignity.

…return home.

…maintain hope and determination.

Setting

What does the time of year have to do with the story?

How does the weather or climate relate to the story?

Is there rain or sun or dust or snow? Is it a dark night or a bright day?

How would it change the story if these elements were switched around? In other words, a bright and sunny day might lead us to believe, at first impression, that everything is great. The weather’s beautiful, so it follows that things are going well. But if they aren’t? What if they don’t?

Pay attention to the surrounding details and how they support and juxtapose the emotional state and tone of what’s actually happening in the characters’ lives.

Consider how the specific space can symbolize pressure on the character, or be a catalyst for how they react. Why do we react viscerally to certain claustrophobic environments - underwater caves, dungeons, to name a few? They’re stifling, we understand immediately how they impact the world of a character. Now apply that as metaphor. How do physical spaces affect the mindset, choices, and actions of a character?

Someday I will write an ode and elegy to phone booths.

Look at the historical context

When does this story take place, and sometimes equally important as the story itself: when was the story written?

We might think of some stories as being old and out of date, but sometimes stories, within the context of the time, were radical or revolutionary or subversive or political in ways that we don’t immediately recognize now.

Look at the geography

A story takes us on a journey. The place it takes us to is both metaphoric and concrete. In other words, the physical place the story takes place at is (probably) important to the story, and likely set there for a reason.

How would one of your favorite stories change if the location was shifted from say, a river to a mountain? From a country home to a city apartment? From Beijing to Mumbai? From Africa to South America?

Intertexuality and Archetypes

You’re going to read a lot of stories and parts of stories that feel familiar, especially the more well read you are. This is intertextualism. It’s the way that writers and storytellers integrate what they have read or watched or experienced into their own work. Whether you recognize it or not, it’s there, and things that may be original to you are (likely) not original per se, but they are referencing, remixing, reusing, interpreting something that has come before. If they do it well, they’re doing it in a fresh and exciting way.

You’re going to recognize a lot of recurring types of characters in the different stories you read. These are archetypes, or archetypal characters.

Physical traits

Why is a character’s appearance described in a particular way, and how is it important to the story? Not talking about their wardrobe. Talking about their physical traits and the things that might make them stand out-scars, limps, missing limbs, etc. How do these relate to the story? Is it immediately evident, or is it something that slowly makes sense the deeper into things you get?

A great story will give you the right amount of information about a character’s physical appearance. You have to ask yourself why they’re included and how they’re relevant to the narrative.

Time travel to the time it was written

This might be one of the most helpful tips I can offer about experiencing a book or film to the fullest. What I mean is that stories have been told in some form for thousands of years. Those thousands of years span an incredible range of cultures, ideas, and mindsets.

When we read some stories now, some of these ideas and mindsets or characters or ways of doing things seem horrific or archaic or unconscionable or indefensible. We judge them according to what we know and experience now. There is a place for that, for examining the ways in which attitudes change, language evolves, the normal becomes the outlier, the way that throughout history there are peoples and voices that are suppressed or relegated to the margins or left out altogether…

…and yet we must, we must also try and consider not only the story itself, but the time in which it was written, and what that says about the way we interpret and respond to the character and situations occurring within it.

We can re-examine and reinterpret and new ways of analyzing art and literature from the past, but we also have to possess a willingness to examine the time, mindset, and culture any work was written in.

Listen to the tone

Irony is a universal umbrella that covers everything. It is a root of much that is witty and interesting. Irony helps set a tone, and it’s important to understand what the tone is so you can fully engage with what is intended to be communicated to the reader. Otherwise, we miss the significance of what’s happening, because irony means that what is said or what is happening is contrary to what expect to be said or what is actually happening.

In other words, irony conveys something that is the opposite of what is being said or done or what is expected. That’s why it’s so important to understand the tone of what you’re reading so you can recognize and engage fully with what is really happening.

A summary of reading for enjoyment and learning

Reading should be fun. Sometimes, like with playing or doing anything enjoyable, you have to put in a little bit of work. But that little bit of work will pay off and make for a richer experience if you make a little roadmap for yourself ahead of time and commit to a little bit of thoughtful introspection about what a story is about. Here’s five things to consider when you’re reading for both enjoyment and learning.

Read slow enough to process what you’re reading. If you’re reading for a combination of pleasure and learning, then you might need to slow down your pace enough to process some of the elements we’ve talked about above. In other words, if you’re racing through a great thriller - which is great too - you’re anxious just to know what happens next, and therefore you’re probably not spending as much time considering the motivations of characters or the role of setting, or the type of symbols being reiterated. That’s a different kind of reading. So slow down. If you need to read a little bit at a time, then take a break for an hour, or a day, then do it. Give yourself time to process what you’re reading.

Steal from The Scientific Method. In other words, ask some questions and develop some hypotheses, as you read, about what the author is trying to say. Look for clues from language, setting, symbols, recurring motifs, etc. What is it about under the surface, what themes do you see popping up?

Don’t steal from Wikipedia (or the interwebs). In other words, don’t cheat yourself by reading other interpretations or analyses first. Gather your own thoughts only from the story before jumping to the response from other readers. Note: I am a big fan of keeping a dictionary close by, however. It makes a difference to look up words you don’t understand as you’re reading. That way, you’ll increase your vocabulary, as well as having an even stronger idea of what the author is trying to say and why they chose the language they did.

Write down your notes somewhere. You have a terrible memory. Trust me. You do. Almost everybody does. When you read something intriguing or thoughtful or puzzling or difficult, jot it down - even if it’s just a page reference and a single word. Give yourself an easy way to circle back to the parts that grabbed you. Otherwise, you’ll forget most of them. You will.

When you’re done, jot down a few things that grabbed you. Write down your impressions. They can just be for you. In bullet points, in haiku, in sentence fragments, whatever you want. This is tied into #4: you have a lousy memory. If you invested the time to read a good story (or a lousy one), take several seconds at the end to summarize in some form your impressions. Super brief if you want. It’s good for your memory and critical thinking skills. In fact, I bet it’s also great for your imagination and brain in general. But don’t quote me on that.

Leave here and find a good book. Happy reading!

——

Other relevant pages below